The Amistad Art Gallery on the first floor of Du Bois College House, under the leadership of Faculty Director Amalia Dache, previously housed the following exhibition in Fall 2023:

LA RUMBA QUE TRAJÓ EL BARCO

"The Rumba brought by the Ship"

Title: La Rumba Que Trajo El Barco “The Rumba brought by the Ship

Artist & Photographer: Juan Caballero – La Habana, Cuba - NYC

Text, curatorship, and museography by Santiel Rodriguez Velázquez

Amistad Gallery W.E.B. Du Bois College House. University of Pennsylvania

La Rumba Cubana series

The Cuban Rumba series. According to data, the Rumba in Central Park New York City began in the early sixties, where it initially included the participation of groups of people who loved Cuban music. Many were Puerto Rican and from other Latin countries. At the beginning of the eighties, people belonging to what was called the Marielitos group began to appear. They were from Havana and other provinces and came to the United States through the migratory exodus that occurred in 1980. Of this group of Cubans, the majority settled in the State of Florida and the City of New York. In the early eighties, people from this group who emigrated to NY discovered the Rumba in Central Park and began to spread the word to the rest of this cultural manifestation, and as a consequence there was a large participation of Cubans that has lasted to this day. They are in charge of a reunion with the true essence of what the true Cuban Rumba is. Many of the people who came to the park for the first time have already died and others have grown old, and the youngest people who came to the United States in the years still participate. The Central Park Rumba has been a powerful tool and a way for these Cubans to keep their traditions alive. Many of this group were not rumberos in Cuba but had grown up in the rumbero environment of poor neighborhoods of Havana, and discovering this event brought them a reunion with their roots and traditions. A curious fact is that the majority of the Marielitos who felt close and identified with the rumba preferred to come to live in New York City and not in Miami like the rest of the emigrants from that group from Mariel. Possibly they felt that they might have a better chance of surviving in NYC than in Miami. In 2016, Cuban Rumba was recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Heritage of Humanity. However, when practiced in the Cuban diaspora of New York or Miami, it has other connotations, evoking the longing for a lost homeland, in addition to creating a great platform for people from Latin America and from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds to come together in the same space of community interest.

Written by Juan Caballero

1980 marked a before and after in the migratory history of Cuba. From those warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, crossing the Straits of Florida; prows heading north about 1,700 ships with a little more than 125 thousand Cubans carrying very few material belongings, yet their spiritual belongings as heavy as an anvil were carried in the heart of each one of them. The sound of an Ilú Batá, the rhythm and clave of the guaguancó, yambú, columbia, its jiribilla, the tinkling of a cowbell, the strength of the bass of the cajón, the dance of an Íreme, a Congo, and the procession of the vacunao that seduces at the climax of the rumba and falls in love.

On a Sunday afternoon, after several days evaluating the possibility of a trip, we arrived at Central Park in New York City and taking the suggestion of the current exhibit’s photographer Juan Caballero, I hoped to meet and spend time with those Cuban rumberos belonging to that great migration of the '80s; many of them who were dispossessed from marginalized Cuban neighborhoods and many were also initiated into the foundations of African religions inherited from our ancestors. Some Abakuas, others practitioners of the Ifá-Orisa religion and if that were not enough, many Mayomberos. I thought about those who were once uprooted from the land that saw them born and re-emerge in a strange land with a lot of pain, but also with freedom and a great desire to move forward. Being happy to be alive and making the same music as always, as if they never would have left Cuba.

To my surprise, I found a great variety of nationalities. From a Puerto Rican to a blonde American who plays the tumbadora like a Cuban, converging in a multicultural environment. I observed without a doubt that the rumba was present, but it was no longer just ours, it now belonged to the regulars in New York City's Central Park. The rumba was already for those who wanted to dance and sing it, even if it was not their tradition.

I imagined in that case, that "in 43 years many things can happen", among them the adaptation of these rhythms to the cold northern climate, where "you can't play the rumba every day" and even less so in Central Park in the middle of the New York winter. Adaptation, yes adaptation! Once again migration, this time semi-forced and part of that adaptation, was also that spontaneous amalgamation of nations, idiosyncrasies and ways of thinking, transcending to more human spaces, creating community.

Rumba came to New York City to be inherited, not only by those children of Cubans who arrived in the 80s and 90s, but also by those who adopted it, gave it shelter in their homes, in their souls and in those who, like the photographer Juan Caballero, have fallen in love with this social phenomenon, where time in rhythmic conjunction stops being a spatial element, and is transformed into a harmony that gives life.

The work of this passionate photographer is evidence that in these 43 years we have not only been able to enjoy this transculturation in a foreign land, this mixture of roots that his photos narrate, but also that rumba continues to be a vigorous source to the human being, from the effusion that emanates from the soul of each rumbero.

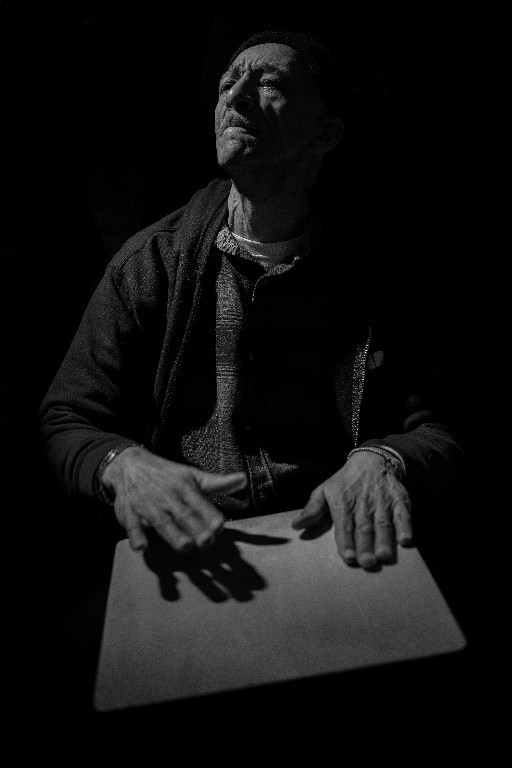

In the composition of these snapshots are carved the courage that Juan knows how to glorify, in singing, in playing the drum, in dancing and in the enjoyment of a good rumba. Between lights and eclipses, Juan manages with his lens to capture the essence of that intimate space that each rumbero leaves his mark on the tumbadora, in a drawer or in his own voice that detaches itself from the personal to be delivered to the world. Far from the commercial and well-rooted in respect for what is inherited, this humble hunter of illustrious moments has managed to capture the hands, gestures and even the sound waves of those who sing with fury, those who are always present “cuando la Rumba les llama”, of those who will be rumberos one day, of others who are no longer among us, but were emissaries of what we can delight in today. From a Oro Iyá Ilú Batá, to traditional dances, whether outdoors or in a specific environment, its lens has been equipped with multiple scenarios where spontaneity reigns, but in communion and effort with customs, in which not only the qualities of these habitual manifestations are appreciated, as well as those of that prelude of effulgence well-aimed by his eyes and his instant cunning.

We cannot talk only about rumba without alluding to the respect of those who were and always will be “The Great Ones.” Because the rumba is not only inherited, the rumba is also a tribute to the ancestors, but not with religious characteristics. However, it has a spiritual link for some of us who practice these “magical” religions of African origin. We understand that death is just a transition to another state, to another time invisible to the eye that is used to seeing matter, to that state where it is possible to encounter “the truth in the world of the ancestors.” For a rumbero it is familiar to have these beliefs, therefore, a rumbero does not say goodbye with tears, a rumbero says goodbye with music and dance, not celebrating his death, but rather the journey of his life, the legacy he left in our culture, which has transcended the borders of insularity to become multinational.

It is true that we would not have enough walls to reveal Juan's magnificent and extensive graphic work in these contexts. A feat of many years capturing rumba through the diaphragm, through time and its beautiful illuminations, in the corners and parks of the immeasurable City of New York. But what we do is offer a graphic and sound testimony of what was, is and fortunately will continue to be, La Rumba que Trajo el Barco.

Lic. Santiel Rodríguez Velázquez

Artist Bio

Juan Caballero Cabrera was born in Havana, Cuba. In 1994 he took his first steps into the world photography on a trip to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Soon after Caballero began studying with the Association of Photographers of Buenos Aires, and later worked as a photographer for the "Argentina Foundation to Aid Immigrants." With this group he covered the First National party for refugees in Argentina and his photos were published in their magazine. It was in Argentina working with refugees from around the world that he first realized the powerful impact a photo has, effectively documenting a country's social and political realities. In 1997 he returned to Cuba to study at the International Institute of Journalist José Martí.